When Teachers and School Counselors Become Informal Mentors, Students Thrive

For years, the research has been clear: Teacher-student relationships matter. And now, a new working paper shines more light on just how important these relationships can be for students’ academic success.

Some students form deep connections with their teachers, counselors, or athletic coaches, who are often the adults they see most often aside from family. And those bonds may organically develop into an informal mentorship, in which educators support students both academically and socially. These types of relationships, experts say, will be particularly important this fall as students return to school still grappling with trauma from the pandemic.

Indeed, according to a national longitudinal study, more than 15 percent of adolescents identified a teacher, counselor, or coach as the adult who, other than their parents or stepparents, had made the most important positive difference in their lives. About 90 percent of the reported school-based mentors were counselors or teachers, and students were most likely to have met them toward the end of 9th grade or the beginning of 10th grade.

“These relationships last for many years in the vast majority of cases, and in many cases, well after students graduate from high school,” said Matthew Kraft, an associate professor of education and economics at Brown University and the lead author of the working paper. “We know these are not just interactions that are part of teacher-student relationships inside the classroom or on the sports field or in the counseling office. … School-based natural mentors go above and beyond and step outside their formal role.”

Yet the students who research shows would benefit the most from mentoring—namely students from low-income families—are less likely to have access to those types of relationships.

Kraft, Alexander Bolves of Brown University, and Noelle Hurd of the University of Virginia analyzed data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, which followed a nationally representative sample of middle and high schoolers for three decades, starting in the 1994-95 school year. While their analysis is not proof positive of a causal effect, Kraft called this “the most robust empirical evidence to date” on the relationship between school-based natural mentors and students’ long-term success.

The respondents commonly said their school-based mentors gave them advice and guidance, encouraged them to stay out of trouble, and helped them grow up. These are often long-lasting, close relationships—80 percent of young people said their mentor remained actively important in their lives after they graduated from high school. The educators helped shape students’ identities, notions of self-worth, and moral values, respondents said.

Mentoring is “individualized and different for every kid,” Kraft said, but school-based mentors often help students with their homework, offer advice, and support them as they apply to college and navigate the financial aid system.

And it works: The study found that when students have a school-based mentor, they are more likely to pass their classes, earn more credits, and earn a higher GPA. And in the long run, they are 15 percentage points more likely than students without mentors to attend college and complete almost an entire year of higher education.

Students don’t have equal access to natural mentors at school

The study found that Black and Latinx students, as well as students from low-income families, were less likely to report having a school-based mentor. White and Asian students—particularly Asian male students—from more-affluent families were the most likely to report being mentored by an educator.

Kraft said it’s not surprising that fewer students of color have a school-based mentor because past research finds that mentors and mentees often share similar backgrounds. The teacher workforce is comprised mostly of white women from middle- and upper-middle-class backgrounds.

Past research also finds that adults are more likely to mentor adolescents whom they see as being academically gifted, physically attractive, outgoing, and easy to get along with. Yet teachers often have implicit racial biases, and studies have shown that many perceive Black students as angry when they’re not.

Hiring more teachers of color, Kraft said, could help improve students’ access to school-based mentors.

“I think there’s a real paradox in the promise that mentoring holds,” he said. “These are more likely to be relationships that white students and students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds develop. However, we also find evidence that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds appear to benefit most from natural mentoring.”

School-based mentors are particularly beneficial to Asian male students, the study found, and Kraft said more research is required to find out why that is. The study also found that students from low-income families see even greater benefits than their more-affluent peers when it comes to reductions in course failure rates and an increase in college-going rates.

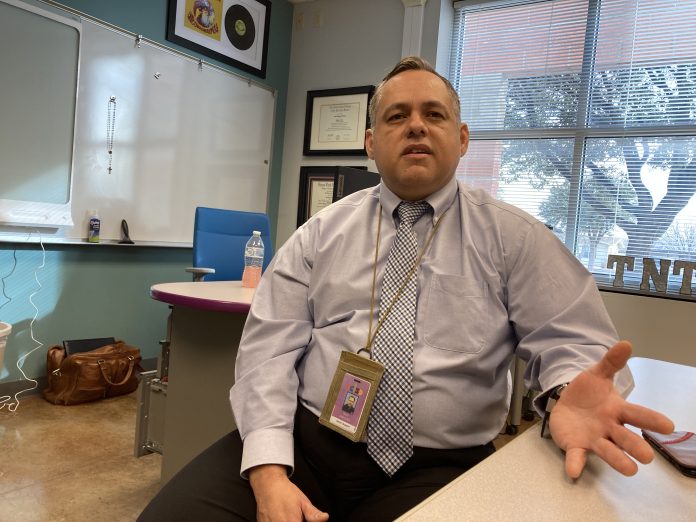

Jennifer Kline, a counselor at Festus High School in Missouri, said she makes herself available to all students who need help with homework or a safe space to decompress. Students who don’t have strong support at home often are the ones who take her up on that offer, she said.

“I meet the needs of all my students, but I tend to find the ones who need that little bit extra and spend that time with them,” she said.

For instance, Kline developed a relationship with one student who transferred to Festus High School partway through her freshman year. Over time, the girl, who had been to 18 different schools and was placed in foster care at age 16, began confiding in Kline, telling her things she had never told anyone else. Kline helped make sure the student had more structure in her life, and eventually, she began to succeed.

That student had a 60 percent attendance rate when she started at Festus High School, but by the time she graduated, she had a 98 percent attendance rate and had earned all As and Bs her senior year. She went to community college, and is now working to earn both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work. Kline still keeps in touch with her.

“As soon as you treat them as a person, they start to realize you care,” Kline said. “When they know someone’s on their side, they don’t want to disappoint you.”

Mentoring is more common in certain schools

The prevalence of mentorship in school communities varies significantly, the study found, with mentoring rates more than twice as high in some high schools. The authors found three significant predictors of why mentorships develop in certain schools more than others:

- Students have a strong sense of belonging in the school community.

- Class sizes are smaller. The study estimates that for every 10 fewer students in a classroom, the probability a student forms a mentorship with an educator increases by about 20 percent.

- There are more sports teams for students to join.

Kraft said school leaders should also focus on fostering a diverse and supportive school environment where educators have the capacity to engage in these informal mentorships. But leaders shouldn’t try to force these relationships, which by definition are naturally developing, Kraft warned: “It wouldn’t be authentic if we tried to take a more heavy-handed approach.”

This fall, students are expected to return to classrooms dealing with trauma, with many having fallen behind academically during the pandemic. Strong educator-student relationships will be key to helping students thrive, Kraft said.

“When we think about what an effective school is and does, we need to expand our vision beyond what happens inside of classrooms and on playing fields to those types of relationships that take place on the margins of schooling,” he said.